David Fincher fans have had plenty to celebrate over the past few months. September marked the 25th anniversary of Se7en, Fincher’s deeply disturbing psychological thriller that established the then 33-year-old as one of the most iconoclastic young directors in Hollywood. Then, just a couple of weeks later, The Social Network, Fincher and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin’s searing exploration of Mark Zuckerberg and the origins of Facebook, turned 10. Most exciting of all for Fincher aficionados, though, is the fact that, more than six years after the release of his last feature film Gone Girl, Mank will finally arrive on Netflix on 4 December.

More like this:

- The real ‘heart of darkness’

- The film that showed a US in chaos

- Why film and TV get Paris so wrong

Fincher has waited around 20 years to find the perfect home for the film, which was originally written by his father Jack in the late 1990s. But while most major Hollywood studios were put off by the idea of a black and white biopic of Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman J Mankiewicz, Netflix gave Fincher carte blanche to fulfil his vision.

The Guardian gave Mank five Netflix)

The early reviews for Mank have been extremely positive, and Fincher has immediately become one of the main contenders for the best director Oscar. Covid-19’s disruption of the 2020 cinematic calendar means that Fincher’s competition isn’t quite as strong as it could have been. But it’s to the Academy Awards’ great shame that this titan of modern filmmaking has somehow only received best director nominations for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button and The Social Network. Despite this oversight, Fincher’s place in the cinematic pantheon has long been secure. No other modern filmmaker has examined alienation, depression, obsession, and the dark side of intelligence like he has, while keeping a stylish, visceral, and, most importantly of all, entertaining approach.

But what is it that sets Fincher’s work apart from that of his peers? For cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth – who first worked with Fincher on the 1989 Madonna music video Oh Father as a camera assistant before shooting Fight Club, The Social Network, The Girl with The Dragon Tattoo, and Gone Girl – it’s how he challenges his audience to examine their own vulnerabilities.

His movies are not always clean and precious and wrapped up – Jeff Cronenweth

“He puts them right out in front so we have to kind of absorb them. Even though we don’t necessarily like them,” Cronenweth tells BBC Culture, before explaining how, at the end of pretty much every Fincher film, you’re left to ask what was the right or wrong course of action, and whether or not you’d have acted in the same manner. “Those questions make for good discussions and conversation, but they also make people uncomfortable. His movies are not always clean and precious and wrapped up.”

Fincher’s dark and mysterious reputation, generated by his films, is at odds with the “enormously passionate, sensitive guy” who Cronenweth calls a great friend. “Because he chooses subject matters that push people’s buttons, you can easily brand him this callous, cold-hearted, dark person. In reality that’s not him at all. He perceives that. He’s aware of it. He studies humanity. But to say that his movies are cold and without passion or humanity just shows that you haven’t seen the movies. He studies the dark parts of it and presents them to us. That’s the whole point. He wants to study these fallacies that we all have.”

In telling the story of the manhuAlamy)

Fincher’s interest in this aspect of the human psyche was sparked because he grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when the Zodiac Killer terrorised the region. He meticulously detailed this period and story in 2007’s Zodiac, and then continued to explore the mental process of serial killers in Mindhunter’s two-season run on Netflix.

For Laurence Knapp, film studies professor and editor of David Fincher: Interviews, the final scene of the first season of Mindhunter, which sees Jonathan Groff’s Holden Ford having a nervous breakdown because of how much he relates to the murderer Ed Kemper, is Fincher’s way of acknowledging the danger of “getting too close to this material”, and how you can reach a point where you lose your “bearings and balance and sense of self”.

Smart take

While Fincher’s point of view is undoubtedly unique, and his ability to mesh it with Hollywood’s mainstream demands even more so, his rise from music video and commercial director to cinema has also been integral to his success. Knapp says his journey, and the work ethic it required, separates him from the other filmmakers, like Kevin Smith, Quentin Tarantino, Steven Soderbergh, and Richard Linklater, who also emerged during the mid 1990s.

“He was very savvy in terms of getting into music videos and then getting into features through there. He has a craftsmanship and attention to detail, which you don’t feel as much with the other filmmakers,” Knapp tells BBC Culture. “He is very prescient in terms of industry changes and practices. Look at how he jumped on to Netflix so early with House of Cards.”

It was while making commercials and music videos that Fincher learnt how to truly collaborate and trust his production crew, too. As Knapp points out, Fincher might be a “consummate filmmaker” who is always “highly conscious of the editing, sound, and the work as a whole”, but he has always shown a “remarkable facility for collaborating, while still clearly maintaining his own authorship”.

According to Variety’s review, Mank is “a tale of Old Hollywood that’s… steeped in Old Hollywood – its glamour and sleaze, its layer-cake hierarchies, its corruption and glory”

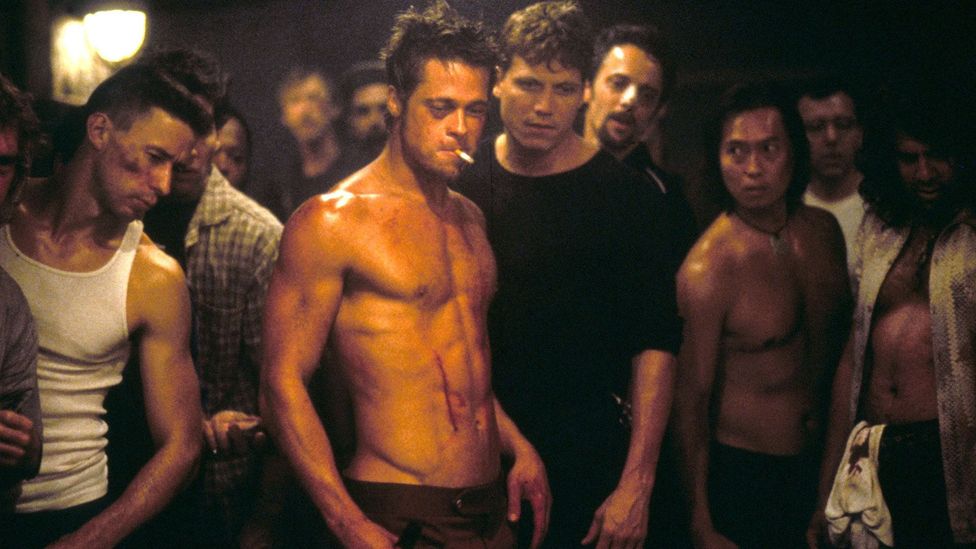

But what is it actually like to work with Fincher throughout production? Laray Mayfield has been an integral part of Fincher’s collaborative process since he hired her to be the casting director on Fight Club. Mayfield, who had previously worked as Fincher’s assistant before the 1999 adaptation of Chuck Palahniuk’s novel, says that Fincher’s collaborative skills extend to the other side of the camera, too. “He really loves actors, and he knows a lot about actors.”

Fincher’s main focus is on the script and its characters, though. Way before filming, Fincher and Mayfield sit down and dissect the screenplay from the point of view of every character. They ask, “Who they are. Where they came from. What’s their backstory. What they want to accomplish. Where they are emotionally,” all in order to understand them and to figure out, “how they move the story. How they interact with other characters. As well as the place they hold in the story.”

Based on the 1996 novel by Chuck Palahniuk, Fight Club wasn’t initially a box office success, but DVD sales made it a cult hit (Credit: Alamy)

Fight Club also marked the first major Hollywood production that Cronenweth had worked on as the director of photography. Unsurprisingly Cronenweth learnt a lot during the shoot, but his main takeaway arrived in a surprisingly calm manner. At one point, Cronenweth believed that a scene was too dark, while Fincher insisted it was too light. When it proved to indeed be too dark, Cronenweth assumed he was going to be fired, since he was unable to articulate the problem and should have been more upfront.

Instead, Fincher turned around and said, “You know what? You can’t push boundaries unless you take a risk and we took a risk and we’ll do it again tomorrow. You’re gonna make mistakes sometimes when you’re creating art.” That “really liberated” Cronenweth’s approach to making movies. “People can let fear get to them. It stops them from accomplishing their goals. But, for me, if it keeps you on your toes, if it keeps you alert, if it keeps you innovative, and keeps you from repeating yourself, you can use it as a tool. I think it keeps us on point and progressive.”

Fincher is the therapist to American society because he is keenly aware of the audience and is able to communicate with them – Laurence Knapp

Mayfield has always noticed how Fincher only wants to work with “vital and important” people that are intent on solving problems on his set. “We don’t work for David, we work with David. We’re there to support the vision and, with our departments, move forward. Even on the hard days.” Ultimately, though, Fincher is fully aware that the “buck stops with him”, says Cronenweth, and he “takes ownership of the good, bad, wrong, or right of all of his movies.”

Luckily for Fincher, most of his output has been adored by audiences and critics alike. Knapp believes his impact stretches far beyond the mere craftsmanship and beauty of his visuals or the smart and thought-provoking subtext that’s layered throughout his work. For him, Fincher is “the therapist to American society”, a mantle he has taken from his great inspiration Alfred Hitchcock, since “he is keenly aware of the audience and is able to communicate with them and sell his work”.

Meanwhile what Mayfield finds most inspiring about Fincher, above and beyond the fact that his films mean his name is “already etched in cinematic history as one of the great directors ever”, is his simple regard and respect for getting to fulfil his life-long ambition to be a filmmaker.

“He takes this very seriously. This is a big responsibility. People give you a lot of money to make a movie. David does not take that for granted. That’s another thing with Dave, there’s no excuse not to do things to the very best of your ability. Because it’s a gift that we get to do what we do.”

Mank is released on Netflix on 4 December.

Love film and TV? Join BBC Culture Film and TV Club on Facebook, a community for cinephiles all over the world.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.

And if you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called The Essential List. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Culture, Worklife and Travel, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

0 Comments